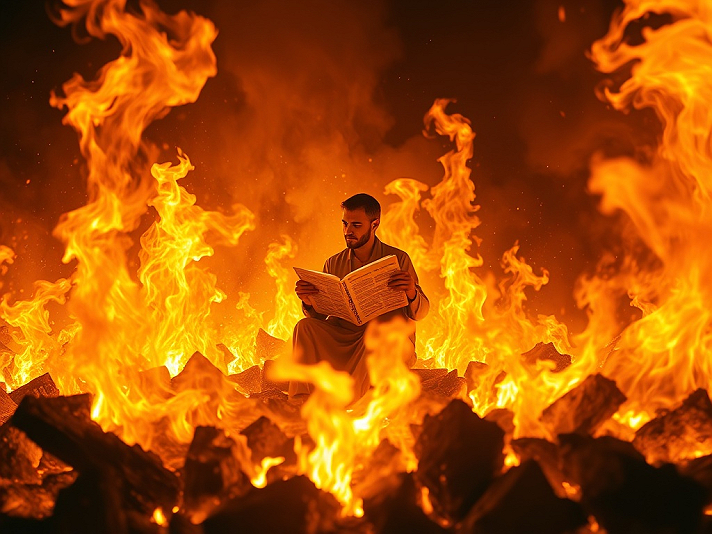

Reading Through the Apocalypse: A Man, a Book, and the Fire That Cannot Touch Him

The image is a single, arresting moment frozen in a storm of fire. A lone man sits cross-legged at the center of an inferno, holding an open book with both hands. Flames rise in towering, almost sculptural waves around him, their orange and gold tongues licking the darkness, yet the man remains untouched. His posture is calm, almost meditative; his head is slightly bowed, his eyes fixed on the pages. The fire does not consume him, and he does not flinch from it. The photograph is a paradox made visible: destruction and serenity occupying the same space, terror and tranquility sharing the same breath.

At the most immediate level, the image is a feat of photographic staging and digital composition. The man’s clothing (a simple, light-colored thobe) is pristine, without scorch marks or even the faintest glow of heat. His skin is unblemished, his beard neatly trimmed, his expression one of quiet absorption. The book itself is perfectly legible, its pages neither curling nor blackened. Every ember that drifts past him seems choreographed to avoid contact. This meticulous unreality is the first clue that we are not looking at a documentary record but at a constructed symbol. The fire is real enough to be believed, yet the man’s immunity to it is absolute. The photograph demands that we accept two contradictory truths at once: fire burns, and this fire does not.

The symbolism operates on multiple intersecting planes. The most ancient and universal reading is that of trial by fire. Across cultures, fire is the ultimate purifier and the ultimate destroyer. To sit unharmed within it is to have passed a test that annihilates everything impure. The man’s posture echoes the seated Buddhas of Borobudur or the yogis in deep samadhi, figures who have transcended the illusions of the body. His book, then, becomes more than an object; it is the source of his invulnerability. Whatever is written on those pages has granted him a knowledge or faith so complete that the material world can no longer threaten him. The fire is not merely physical; it is the fire of attachment, of anger, of ego, of dogma. He reads through the apocalypse because the text has already freed him from it.

A second, more contemporary reading casts the image as a commentary on information in the age of outrage. We live surrounded by digital conflagrations: culture wars, cancel campaigns, viral scandals, endless cycles of synthetic fury. The man in the flames is the reader who refuses to be consumed by the heat of the moment. While the world burns its own house down in recursive anger, he sits in the middle of it, calmly turning pages. The fire is the timeline, the comment section, the breaking-news chyron. His serenity is not ignorance but discernment. He has learned to inhabit the inferno without inhaling the smoke. In an era where attention is the most combustible resource, his attention remains sovereign.

There is also a religious resonance that cannot be ignored. The man’s attire and beard suggest a Muslim scholar or devotee, and the composition deliberately evokes the miraj of Islamic tradition, moments when prophets or saints are granted visions that transcend ordinary physics. The Qur’an itself speaks of Ibrahim being cast into the flames by Nimrod only for God to command the fire: “Be cool and a means of peace.” The photograph restages that miracle for a secular age, asking whether such protection is still possible, whether any text (sacred or otherwise) can still command the elements to stand down. The fact that the book’s pages are legible but unreadable to us heightens the mystery: whatever he is reading is powerful enough to suspend the laws of nature, yet it withholds its secret from the viewer.

Finally, the image functions as a memento mori with a twist. Normally, fire reminds us of mortality; here, it reminds us of the possibility of a consciousness that death cannot touch. The coals beneath him glow like the ruins of a civilization, yet he sits above them as though the end of the world is merely a change of scenery. His concentration is so complete that even the photographer seems irrelevant; the camera is allowed to witness, but not to interrupt. The viewer is left standing outside the circle of flame, holding the uncomfortable knowledge that some forms of attention create a ring of protection no physical barrier can match.

In the end, the photograph does not resolve its contradictions; it deepens them. It is a portrait of radical composure in the heart of radical chaos. It insists that there exists a kind of reading (or a kind of faith, or a kind of discipline) so absolute that it renders the inferno irrelevant. The man does not conquer the fire; he simply renders it beside the point. The flames roar, the coals seethe, the night itself seems to burn, yet the page turns, and the man keeps reading. Whatever is written there is stronger than combustion, older than panic, and quiet enough to silence even the loudest century. The image leaves us with a single, unanswerable question: what must a text say for a human being to sit peacefully at the center of the world’s burning?